Luminor autumn Economic Outlook 2018 | Luminor

Global Outlook: sharpening downside risks

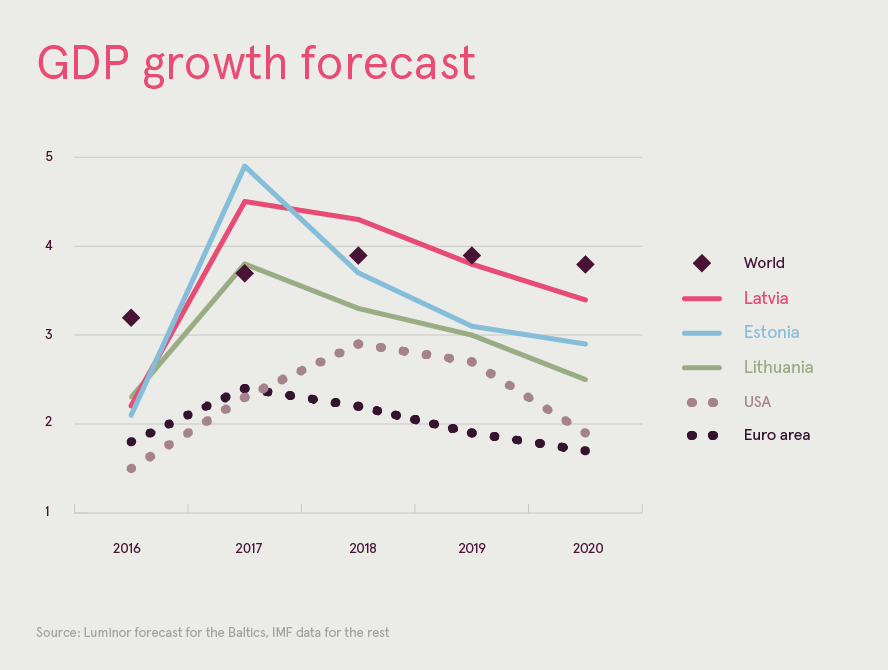

On balance, changes to the world’s economic outlook since our previous report in March have been unfavourable, though moderate. The IMF July forecast for global growth was at 3.9% for 2018 and 2019, exactly matching the one issued in January, but with sharper downside risks. The performance and outlook for different regions have diverged more sharply than previously anticipated.

First and foremost, escalation of trade tensions into a trade war would pose a direct threat to global growth. Though actions initiated by the US government are probably intended mostly to apply pressure to achieve various goals (not only economic), there is a risk that events will get out of hand through rounds of retaliation and counter-retaliation. In this report, we assume that a full-scale global trade war will not occur. If it does, it will have implications for the forecast. While the risks posed by rising USD interest rates to emerging markets were well known, some countries, especially Turkey, but also Argentina and South Africa and others, were not ready for the consequences, with their macroeconomic vulnerabilities being exacerbated by domestic policy mistakes. Now they are facing a risk of recession and prolonged capital flight.

The USA is performing better than expected this year, enjoying the immediate benefits of fiscal stimulus. Annualised GDP growth exceeded 4% in Q2 and seems to remain strong. Fast growth and very low unemployment so far have not translated into strong wage pressures; however, core inflation is creeping upward, exceeding post-2008 heights. Accordingly, two more interest rate hikes this year are likely, with policy makers feeling comfortable to proceed slowly thereafter.

Despite the failure to complete its structural reforms, the euro area’s recovery continues, with the expected moderation of growth rates largely being a normalization towards long-term growth rates. Unlike in the USA, there is still substantial unused capacity that can be absorbed, mostly in southern countries.

Events in Turkey might affect financially weaker euro-area countries through heightened risk awareness in markets, trade links and competitiveness effects of lira devaluation. The persistent weakness of Italy — its combination of slow growth and high debt — remains a threat to euro area stability, leading to periodic jolts of nervousness in financial markets. Some impact may also be felt by the core euro area economies. The recent depreciation of Nordic currencies will exert a negative (though moderate) effect on the Baltic economies. The risk of a no-deal Brexit is rising, along with likely trade disruptions.

We do not expect that these events will significantly affect the new EU member states in Central Europe as these are at a very favourable point in their business cycles: robust growth, very low unemployment, but still moderate inflation in most places.

The Baltics Outlook: on the way to a new Golden Age

These are good times for the Baltics. While we would hesitate to call this a new Golden Age for the region, if similar performance is maintained for a couple of years more, we might make this claim with some conviction. Growth is strong and based on sound fundamentals.

Moreover, there are signs that the region’s economic potential might be greater than generally assumed. Cautious estimates have been based on the assumption that the demographic outlook is very poor. This view in turn supports downbeat estimates about the region’s economy. Baltic countries might be overcoming this predicament as we write our report. Net migration in Estonia has been positive for three years, but now, for the first time, more people are moving from other EU countries to Estonia than vice versa. The population is growing, and growth rates have exceeded the euro area average. After years of massive emigration, Lithuania has reversed the trend this year. A positive migration balance has been registered there for three months in a row. In Latvia there are also indirect signals that migration trends are turning around, in airport and sea port passenger data.

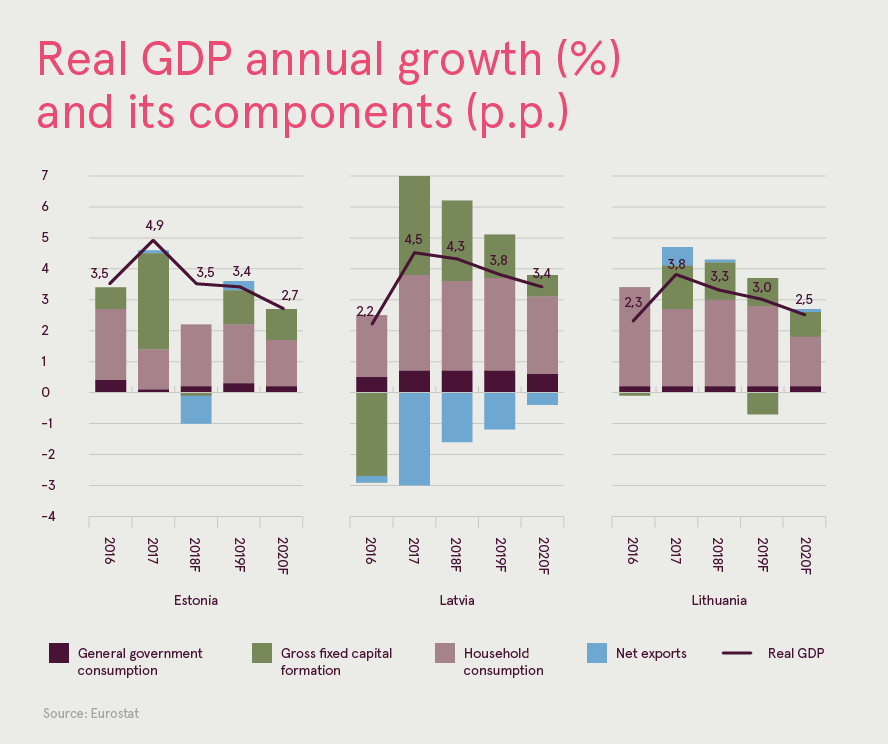

GDP growth in the Baltics has slightly exceeded our expectations since March. We predict a very gradual slowdown in 2019 and 2020, mostly caused by external, not internal factors. Employment is growing, but inflation remains quite moderate overall. Population benefits from the robust labour demand and income convergence with the core EU countries continues.

Consumption growth in Baltics has been moderate and steady, and is likely to remain such. It lags behind wage growth as propensity to save is high (currently with the exception of Lithuania) due to aging. The region has benefited from a strong surge in investment. While the role of EU funds is well known and indeed important, there are also other factors, such as high and rising capacity usage in manufacturing, strong demand for housing and (in the case of Latvia) a pent-up demand for office and retail space. Investment growth in 2018 is slowing down from the giddy pace of 2017, but remains strong, exceeding GDP growth. The flow of EU funds is likely to plateau in 2019 and might decline in 2020, but other favourable factors will remain in force in the absence of a major global crisis.

Growth of overall export volumes has been quite moderate. However, there have been interesting and relevant structural changes. Estonia and Lithuania have continued to show strong progress in high value-added services while Latvia is delivering the expected surge in machinery output. The share of sectors with high potential growth rates is increasing, with favourable long-term implications.

There are obvious medium-term risks that economies will encounter labour shortages. It is unclear, however, to what extent these will slow down growth, and to what extent they will encourage firms to invest and innovate.

Making banking delightfully easy