Lithuania: Better than expected | Luminor

Key highlights

- GDP growth remains robust and broad-based with private consumption, investments and exports all making a positive and fair contribution

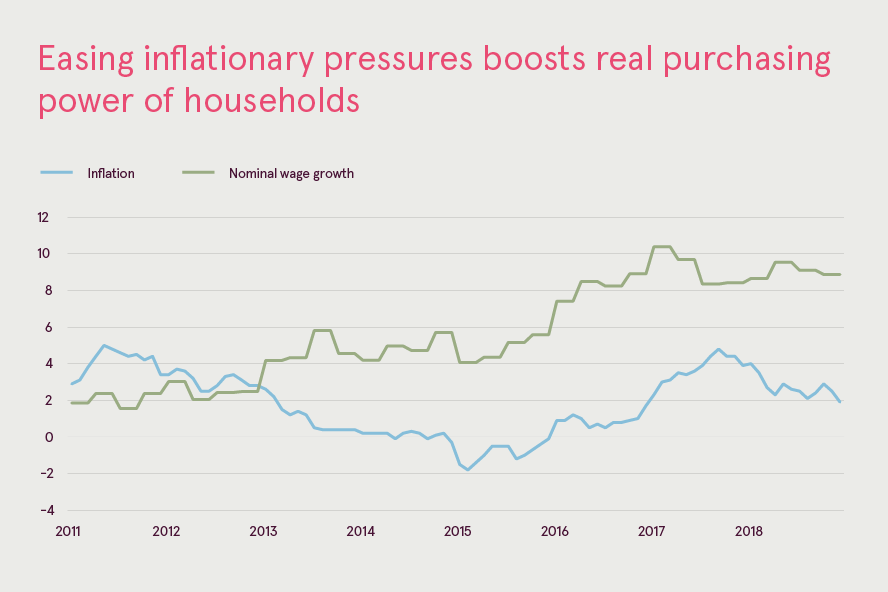

- Easing inflationary pressures and solid wage growth keeps strong momentum in retail trade growth, which was the highest in the European Union in 2018

- Contrary to consensus forecasts, employment growth turned positive in 2018 thanks to rising immigration, falling unemployment and increasing labour market participation rate

- Net international migration deficit fell to a record low in 2018 (-3.3 thousand) and is expected to turn positive in 2019 - for the first time in 30 years

- Productivity growth accelerated and caught-up with wage growth, which helps keeping international competitiveness

- Easing inflationary pressures suggest that a vicious price-wage spiral is losing its velocity

- Lithuania has no discernible internal or external imbalances: public and private debt levels are exceptionally low and there is no credit, inflationary or real estate bubbles

- Public deficit will remain in surplus territory in 2019 and 2020 despite implemented tax reform

- Key risks stem from external environment, since post-crisis export-driven recovery made Lithuania an increasingly open economy, dependent on the health of and access to external markets

- Long-term growth potential might be larger than generally assumed if vicious cycle of emigration will be transformed into a virtuous cycle of immigration (and re-emigration), which would alleviate pressures on social security system and sustain an ongoing boom in real estate sector

Five reasons why we upgrade growth forecasts

Lithuanian economy performed better than expected in 2018, but changes were not due to one-off events, but rather of positive longer-term trends, which compelled us to increase growth forecasts for 2019 and 2020. There are five key reasons why we made these changes:

- Easing inflationary pressures. Annual inflation rate fell from an alarming 4.5% observed in mid-2017 to a vicinity of 2.0% in the beginning of 2019. Lower inflation boosted purchasing power growth of households and resulted in a rebound of retail trade growth, which accelerated to 6.6% in 2018. We forecast inflation to remain close to 2% in 2019 and 2020 due to rising competition in retail trade sector, lower oil and food prices as well as dwindling growth of service prices. Falling inflationary pressures should slow-down a vicious price-wage spiral as employees are less likely to demand an ever greater increases in wages to compensate them the loss in purchasing power due to rising prices. This, in turn, should contribute in sustaining Lithuania’s international competitiveness.

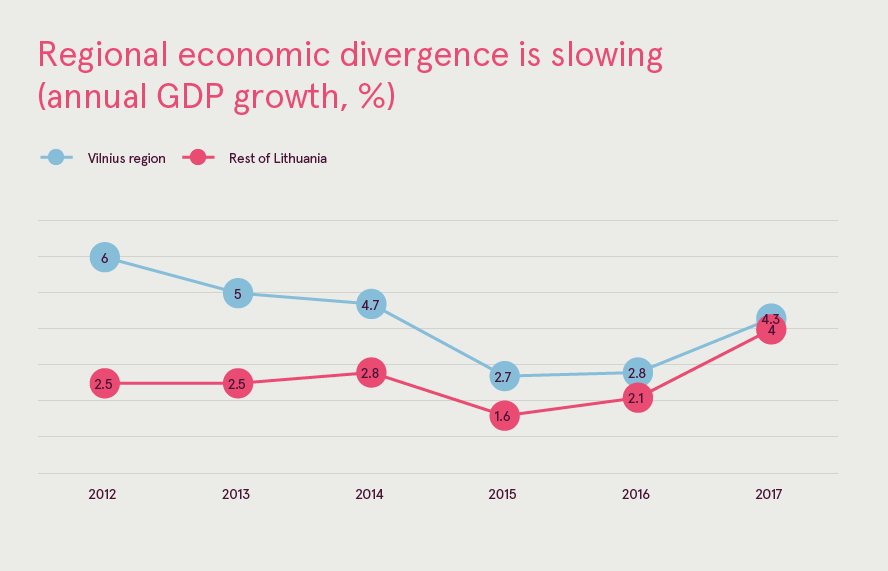

- Less regional divergence. Regional economic divergence has been one of the key bottlenecks for Lithuanian economic growth during the post-crisis period. For example, GDP growth in 2012-2016 averaged 4.2% in Vilnius region compared to a mere 2.3% in the rest of Lithuania. Uneven economic development increased social tensions, emigration and risked making Lithuania a one-city state. However, in recent years growth has increased in other Lithuanian regions, notably Kaunas and Šiauliai, which significantly reduced regional economic divergence. The revival of Lithuanian regions can primarily be attributed to increased investments into manufacturing sector, which primarily is located outside Vilnius region, as well as an increase in service exports (transport, IT etc.). Lower regional divergence has a potential to boost overall economic growth as well as increase its sustainability. Revival of regional growth also contributes positively in stemming emigration.

- Improving demographic outlook. We reiterate our call made last autumn that downbeat estimates of Lithuania’s long-term growth potential are often being made based on overly-pessimistic demographic outlook assumptions. We proved to be right as employment growth in 2018 was substantially faster than consensus forecasts. For example, European commission expected the number of employed to shrink by 0.4%, but instead it rose by 1.8%. The main reasons were increased immigration, higher labour participation rate and lower unemployment rate. These trends are expected to continue with net international migration expected to turn positive (for the first time in 30 years) already in 2019. Consequently, vicious cycle of emigration may be transforming into a virtuous cycle of immigration (and re-emigration), which could give a sizeable boost to Lithuanian economy and cool down overheating labour market.

- Higher usage of EU funds. There are increasing worries about the potential negative effect on Lithuanian economy of the reduction of structural EU-aid after 2020. However, Lithuania is very slow in utilizing existing EU-aid from 2014-2020 period – only around 60% of EU funds have been utilized. Hence, it is likely that during the period in 2020-2022 Lithuania will have a sudden increase (rather than decrease) in the usage of EU funds as authorities will rush to utilize remining funds before the deadline in end-2022. This will temporarily boost GDP growth in general and investments in particular. However, there is a substantial risk that EU-funds will not be used efficiently and hence will not be long-term value generators.

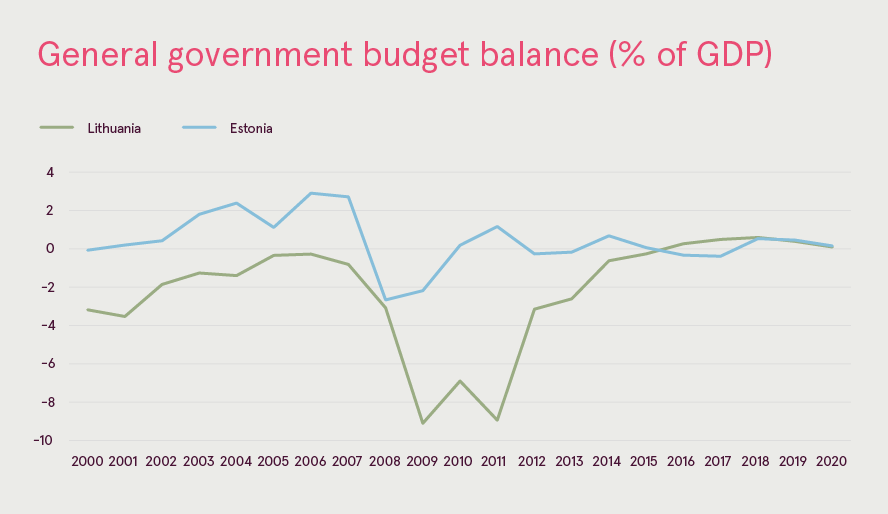

- “Estonisation” of Lithuanian public finances. Lithuania has been among the worst performers in the Baltics habitually having the largest public deficit and debt levels. This is well illustrated by the fact that Lithuania was the last country to meet Maastricht criteria and adopt euro. However, fiscal stability law and faster than forecasted GDP growth resulted in accumulated budget surpluses, which led to a continuous reduction in public debt levels. Moreover, cheaper financing costs lowered debt interest payments from 2% of GDP in 2012 to a mere 0.9% of GDP in 2018. Having also already achieved a goal to spend 2% of GDP on defence, larger share of government spending can be devoted to finance education, health and social security. Given higher than expected GDP growth, we expect budget surpluses to continue in 2019 and 2020.

Risks are mainly external ones

Lithuania has no visible internal or external imbalances: public and private debt levels are exceptionally low and there are no credit nor inflationary or real estate bubbles. Belt-tightening policies implemented during the post-crisis period, influx of foreign direct investments and more broad-based growth transformed Lithuania from one of the most vulnerable to one of the most resilient regions in the EU. Yet export-driven recovery also made them increasingly open economies, dependent on the health of and access to external markets. An ongoing trade and sanctions war with Russia as well as emerging market weakness also made them increasingly dependent on the EU, hence economic performance of Lithuania to a large extent will depend on economic health of the single market. In this context, Brexit poses a real, but limited challenge. Even in hard Brexit scenario the effect is expected to be limited to no more than 0.5% of GDP. The more serious threat is the unity of the remaining EU countries, which, in times of increased protectionism, is especially important for such a small and open economy as Lithuania.

We expect economic growth to remain robust and broad-based with private consumption, investments and exports all making a positive and fair contribution. Export growth is expected to moderate, but a recent influx of foreign direct investments and higher usage of EU-funds wll act as a mitigator. Longer-term growth potential will very much depend on how successful Lithuania will be in implementing productivity-enhancing reforms, especially in education and health sectors, as well as in attracting labour and capital, which would facilitate an ongoing income convergence with the West. This will not be an easy task, since given existing demographic situation, Lithuania has to fight two fronts at the same time: to attract physical capital as well as human capital.

Making banking delightfully easy